The Chicago Harbor Lighthouse: Silent Guard

Strolling along

By the teeming docks,

I watch the ships put out.

Black ships that heave and lunge

And move like mastodons

Arising from lethargic sleep.

Carl Sandburg, Chicago’s famous literary son, painted the various aspects of the city’s waterfront life in so many wonderfully vivid and rich colors, textures, sounds, smells, tastes — you name it, he brought it all to life through his poetry. And I thought of his poem “Docks” when I was considering what life must have been like for the lonely lighthouse keepers who tended the Chicago Harbor Lighthouse for nearly a century before it was fully automated in 1979. Located at the end of the breakwater, it still provides a guiding light up to 24 miles out for vessels entering our city, just as it has for over 100 years.

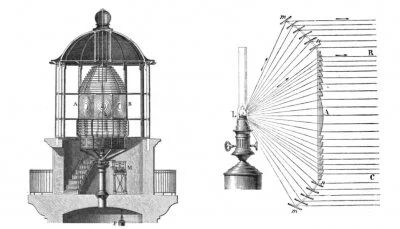

One of only two working lighthouses in the state of Illinois, the Chicago Harbor Lighthouse was built in 1893 to profit from the fame of the World’s Fair, though it was moved to its current location in 1919. A Chicago Landmark on the National Register of Historic Places, it contains a “3rd Order Fresnel Lens” — which is basically a round, 3-dimensional version of a Fresnel lens. The marvelous lens itself also dates from the time of the World’s Fair: it was something of a wonder to fair-goers, despite not being officially “open for business” until the end of the Fair.

The Chicago Harbor Lighthouse’s famous Fresnel lens was originally built for installation in the Point Loma Light, a lighthouse in San Diego. However, after displaying it so proudly at the World’s Fair of 1893, alongside such other “marvels” as Cracker Jack and Juicy Fruit chewing gum, Chicago decided to hang onto the lens for a bit. From what I gather, the lens was officially delivered to the Cabrillo National Monument in California — but only after safe-keeping in Chicago’s hands for nearly a century.

And even though you might not be able to see this famous Fresnel lens in the Chicago Harbor Lighthouse, you can easily find it on a smaller scale: go to any bookstore, and chances are they’ll have some type of handheld magnifying gadget made of plastic. Look at it closely: you’ll see it’s made of many concentric circles, magnifying the image beneath it. That’s a flat Fresnel lens. The giant ones used in lighthouses, invented by French civil engineer and physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel in 1822, essentially work the same way. They take what would need to be an incredibly bulky, heavy lens, and instead cut the lens up into concentric prisms, each one focusing light and amplifying it, while at the same time debulking the lens itself. This technology saved countless sailors for sure! Unfortunately, Fresnel himself died incredibly young of tuberculosis, a mere 5 years after he invented this technology that would revolutionize maritime travel. He was only 39.

So what’s a “3rd Order Fresnel Lens"“? Well, it’s a Fresnel lens…and a big one. Fresnel lenses are measured by seven orders, the largest and most powerful being the 1st Order, and the weakest being the 7th. You’ll find massive 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Order Fresnel lenses in many active lighthouses throughout the country, including the oldest one of all in Boston. That 303-year-old station got a makeover in 1859 with its own massive Fresnel lens, which you can still see today.

As for Chicago’s lighthouse, the 66-foot-tall tower is the oldest part, dating from 1893; the house-like additions, containing a fog signal on one side and a boat house on the other, were added when the lighthouse was moved to its current location in 1918. The northern break wall — that rocky pier-like structure that leads up to the lighthouse — was created to protect the shore (and its ships) from heavy waves; the lighthouse was added to the end of the break wall as further help for the massive ships that would load and unload at the 1916-built Municipal Pier…better known to us as “Navy Pier.”

The Chicago Harbor Lighthouse: isn’t it lovely, silently standing guard in the distance over our beautiful port city?

The oldest part — the 66’ tall tower, from 1893.